Consultant Teachings No. 2: Thoracolumbar Spinal Fractures - A Spine Consult Isn't Always Necessary

Clinical Scenario: You are working one evening in the emergency department when an intoxicated young female is brought in by EMS after being involved in a reportedly high speed MVC. She is clinically intoxicated, uncooperative and tachycardic. She gets a pan-scan CT which identifies some facial fractures and isolated transverse process fractures of the thoracic spine. As you decide on the next steps to take care of the patient, you debate whether to discuss the patient with a Spine specialist.

Clinical Question: Which spinal fractures should you discuss with a Spine specialist? Are there some that do not require any intervention at all?

Literature Review: With the increased availability and increased utilization of CT scanners in the ED, it has become common practice to “pan-scan” patients who present after a trauma, especially those patients who are obtunded/intoxicated or present following a high risk mechanism. The use of the CT scan to identify thoracic or intrabdominal injuries has concomitantly lead to an increase in diagnosis of fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine. As an example, in one retrospective study conducted in the UK of 303 blunt trauma patients who had a Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis CT performed, only six scans (2%) identified thoracic injury and four (1.3%) demonstrated intrabdominal injury while 51 scans (17%) demonstrated an injury to the thoracolumbar spine [1].

With respect to screening for thoracolumbar spinal injuries specifically, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice guideline now recommends CT scan as the primary imaging modality [2]. This is based on a body of evidence that strongly supports that CT scan is more sensitive than X-ray for detection of thoracolumbar spinal injuries. For example, in one small German study of 107 minor trauma patients, radiographs had a sensitivity of only 49.2% and specificity of 54.7% for thoracolumbar spinal injury compared with CT scan which served as "gold standard" [3].

While CT scan is more sensitive, not all the spinal fractures that are found are clinically significant (i.e. requiring spine precautions or bracing/surgical intervention) [4]. For example, in the small German study cited above X-ray alone missed 16/28 fractures of the the mid thoracic spine, but none of these were considered unstable [3]. Of the 94 fractures identified in 51 patients by Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis CT in the UK study, 43 (46%) were considered not clinically significant [1]. Thus, the increased sensitivity of our diagnostic evaluation of trauma not only increases our detection of clinically important fractures, but otherwise stable spinal trauma.

Spine consultation for certain types of stable spinal injuries often comes at the expense of increased patient wait times, prolonged spinal precautions, increased institutional cost, decreased patient satisfaction, and possibly even poorer outcomes if such consultation delays a patient’s transfer to the floor or ICU [4]. Below is a guide to approaching and managing two types of commonly seen fractures in the Emergency Department.

Transverse Process Fractures

Transverse Processes (TPs) of the vertebrae primarily function as sites of paraspinal muscle and ligament attachments. They are part of the posterior column in the classic Denis “three column” classification, which divides the spinal column into anterior, middle and posterior structural elements. The vertebral body consists of the anterior and middle columns and is the main axial load bearing part of the spinal unit. The posterior column consists of the elements behind the vertebral body, with the most important components being the pedicles, facet joints and ligamentous complex. Stability for the spinal column is maintained through a series of attachments between the various spinal elements (anterior, middle and posterior). An isolated TP fracture is a stable fracture and does not compromise spinal stability. Additionally, isolated TP fractures are not associated with neurologic deficits. The spinal cord and nerve roots are not in proximity to the TPs, nor are they at high risk of displacing in a manner that would put the nerve root or cord at risk.

A small 2008 retrospective study from the University of Missouri looked at a cohort of 84 patients with TP fractures; 47 were isolated and 37 were associated with other spine fractures [5]. In this study, no patients with isolated TP fractures required surgery or bracing for spinal stability. Furthermore, none of these patients had any neurologic deficits. The authors concluded that conservative management of isolated TP fractures was appropriate, without the need for orthopaedic or neurosurgical consultation. However, if the TP fracture is associated with another spinal fracture such as a vertebral body fracture, a specialist consultation is warranted for treatment recommendations regarding the associated injury, but not necessarily the TP fracture itself. Of course, a cervical TP fracture that extends into the transverse foramen also necessitates additonal imaging and likely spinal consultation, as it may warrant a CT angiogram for evaluation of vertebral artery damage.

Compression Fractures

Vertebral compression fractures are the most common fragility fracture, affecting approximately 25% of people over the age of 70. Compression fractures are a result of axial force on the anterior column that results in a wedge deformity of the vertebral body. The vast majority of compression fractures do not require surgical intervention. Moreover, these fractures are often stable due to their impacted nature. No study has proven that bracing vertebral compression fractures prevents further vertebral collapse, decreases pain, or improves patient satisfaction. Treatment of most vertebral body compression fractures can focus on reducing associated pain with appropriate pain medications. A thorough approach to a patient presenting with an acute compression fracture should include the following:

1: Patient factors: What was the mechanism of injury (simple fall or high-energy injury)? Is the patient ambulatory, bed or wheelchair bound? Are there significant medical comorbidities (ie morbid obesity, extensive pulmonary disease) that would make bracing an ineffective or even dangerous treatment option? Is the patient’s pain controlled enough to obtain an accurate neurologic exam? Is the patient tender over the spinal segment in question?

2: Fracture factors: Is the fracture stable or unstable? The best way to evaluate is to use the patient’s own physiologic forces to see if there is further displacement of the fracture. Barring any neurologic deficits, plain supine AND upright radiographs of the affected area should be obtained. The goal is to see if there is any significant height loss or increased kyphosis between the series. If not, it’s a safe bet that the fracture is stable.

Given a stable fracture, the next step is determined primarily by patient comfort level. If the patient is able to tolerate sustained physiologic loads (ie sitting or standing), it is reasonable to send them home with observation only, no bracing required. Follow up could be provided by their primary care provider or PM&R. If they are in too much pain to stand or sit despite appropriate analgesia, an extension orthosis (like an off-shelf TLSO) is sometimes beneficial and can be provided by the spine consultant on call. If the compression deformity is acute and deemed to be unstable, if there are any neurologic deficits or other associated spinal pathologies, certainly a spine consultation is necessary and appropriate at that time.

Take Home Points: The increased use of CT imaging, especially in trauma, may lead to the identification of injuries that do not necessarily warrant intervention other than pain control. For neurologically intact patients, it is useful for the emergency physician to be aware of which fractures warrant either bracing or surgical intervention as unnecessary consultation can lead to prolonged length of stay and increased cost without significant benefit to the patient.

Submitted by Chris Cosgrove, Orthopedic Surgery PGY-2

Faculty Reviewed by : Lukas Zebala, MD, Assistant Professor, Orthopaedic Surgery

Everyday EBM Editor Maia Dorsett (@maiadorsett)

References:

1. Venkatesan, M., Fong, A., & Sell, P. J. (2012). CT scanning reduces the risk of missing a fracture of the thoracolumbar spine. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume, 94(8), 1097-1100.

2. Sixta, S., Moore, F. O., Ditillo, M. F., Fox, A. D., Garcia, A. J., Holena, D., ... & Cotton, B. (2012). Screening for thoracolumbar spinal injuries in blunt trauma: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 73(5), S326-S332.

3. Karul, M., Bannas, P., Schoennagel, B. P., Hoffmann, A., Wedegaertner, U., Adam, G., & Yamamura, J. (2013). Fractures of the thoracic spine in patients with minor trauma: Comparison of diagnostic accuracy and dose of biplane radiography and MDCT. European journal of radiology, 82(8), 1273-1277.

4. Homnick, A., Lavery, R., Nicastro, O., Livingston, D. H., & Hauser, C. J. (2007). Isolated thoracolumbar transverse process fractures: call physical therapy, not spine. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 63(6), 1292-1295.

5. Bradley, L et al. Isolated transverse process fractures: spine service management not needed. J Trauma 2008 Oct; 65(4):832-6.

Clinical Question: Which spinal fractures should you discuss with a Spine specialist? Are there some that do not require any intervention at all?

Literature Review: With the increased availability and increased utilization of CT scanners in the ED, it has become common practice to “pan-scan” patients who present after a trauma, especially those patients who are obtunded/intoxicated or present following a high risk mechanism. The use of the CT scan to identify thoracic or intrabdominal injuries has concomitantly lead to an increase in diagnosis of fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine. As an example, in one retrospective study conducted in the UK of 303 blunt trauma patients who had a Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis CT performed, only six scans (2%) identified thoracic injury and four (1.3%) demonstrated intrabdominal injury while 51 scans (17%) demonstrated an injury to the thoracolumbar spine [1].

With respect to screening for thoracolumbar spinal injuries specifically, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice guideline now recommends CT scan as the primary imaging modality [2]. This is based on a body of evidence that strongly supports that CT scan is more sensitive than X-ray for detection of thoracolumbar spinal injuries. For example, in one small German study of 107 minor trauma patients, radiographs had a sensitivity of only 49.2% and specificity of 54.7% for thoracolumbar spinal injury compared with CT scan which served as "gold standard" [3].

While CT scan is more sensitive, not all the spinal fractures that are found are clinically significant (i.e. requiring spine precautions or bracing/surgical intervention) [4]. For example, in the small German study cited above X-ray alone missed 16/28 fractures of the the mid thoracic spine, but none of these were considered unstable [3]. Of the 94 fractures identified in 51 patients by Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis CT in the UK study, 43 (46%) were considered not clinically significant [1]. Thus, the increased sensitivity of our diagnostic evaluation of trauma not only increases our detection of clinically important fractures, but otherwise stable spinal trauma.

Spine consultation for certain types of stable spinal injuries often comes at the expense of increased patient wait times, prolonged spinal precautions, increased institutional cost, decreased patient satisfaction, and possibly even poorer outcomes if such consultation delays a patient’s transfer to the floor or ICU [4]. Below is a guide to approaching and managing two types of commonly seen fractures in the Emergency Department.

Transverse Process Fractures

|

| Source: www. waybuilder.net |

Transverse Processes (TPs) of the vertebrae primarily function as sites of paraspinal muscle and ligament attachments. They are part of the posterior column in the classic Denis “three column” classification, which divides the spinal column into anterior, middle and posterior structural elements. The vertebral body consists of the anterior and middle columns and is the main axial load bearing part of the spinal unit. The posterior column consists of the elements behind the vertebral body, with the most important components being the pedicles, facet joints and ligamentous complex. Stability for the spinal column is maintained through a series of attachments between the various spinal elements (anterior, middle and posterior). An isolated TP fracture is a stable fracture and does not compromise spinal stability. Additionally, isolated TP fractures are not associated with neurologic deficits. The spinal cord and nerve roots are not in proximity to the TPs, nor are they at high risk of displacing in a manner that would put the nerve root or cord at risk.

A small 2008 retrospective study from the University of Missouri looked at a cohort of 84 patients with TP fractures; 47 were isolated and 37 were associated with other spine fractures [5]. In this study, no patients with isolated TP fractures required surgery or bracing for spinal stability. Furthermore, none of these patients had any neurologic deficits. The authors concluded that conservative management of isolated TP fractures was appropriate, without the need for orthopaedic or neurosurgical consultation. However, if the TP fracture is associated with another spinal fracture such as a vertebral body fracture, a specialist consultation is warranted for treatment recommendations regarding the associated injury, but not necessarily the TP fracture itself. Of course, a cervical TP fracture that extends into the transverse foramen also necessitates additonal imaging and likely spinal consultation, as it may warrant a CT angiogram for evaluation of vertebral artery damage.

Compression Fractures

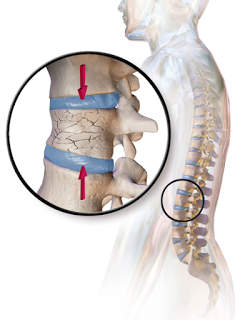

Vertebral compression fractures are the most common fragility fracture, affecting approximately 25% of people over the age of 70. Compression fractures are a result of axial force on the anterior column that results in a wedge deformity of the vertebral body. The vast majority of compression fractures do not require surgical intervention. Moreover, these fractures are often stable due to their impacted nature. No study has proven that bracing vertebral compression fractures prevents further vertebral collapse, decreases pain, or improves patient satisfaction. Treatment of most vertebral body compression fractures can focus on reducing associated pain with appropriate pain medications. A thorough approach to a patient presenting with an acute compression fracture should include the following:

1: Patient factors: What was the mechanism of injury (simple fall or high-energy injury)? Is the patient ambulatory, bed or wheelchair bound? Are there significant medical comorbidities (ie morbid obesity, extensive pulmonary disease) that would make bracing an ineffective or even dangerous treatment option? Is the patient’s pain controlled enough to obtain an accurate neurologic exam? Is the patient tender over the spinal segment in question?

2: Fracture factors: Is the fracture stable or unstable? The best way to evaluate is to use the patient’s own physiologic forces to see if there is further displacement of the fracture. Barring any neurologic deficits, plain supine AND upright radiographs of the affected area should be obtained. The goal is to see if there is any significant height loss or increased kyphosis between the series. If not, it’s a safe bet that the fracture is stable.

Given a stable fracture, the next step is determined primarily by patient comfort level. If the patient is able to tolerate sustained physiologic loads (ie sitting or standing), it is reasonable to send them home with observation only, no bracing required. Follow up could be provided by their primary care provider or PM&R. If they are in too much pain to stand or sit despite appropriate analgesia, an extension orthosis (like an off-shelf TLSO) is sometimes beneficial and can be provided by the spine consultant on call. If the compression deformity is acute and deemed to be unstable, if there are any neurologic deficits or other associated spinal pathologies, certainly a spine consultation is necessary and appropriate at that time.

Take Home Points: The increased use of CT imaging, especially in trauma, may lead to the identification of injuries that do not necessarily warrant intervention other than pain control. For neurologically intact patients, it is useful for the emergency physician to be aware of which fractures warrant either bracing or surgical intervention as unnecessary consultation can lead to prolonged length of stay and increased cost without significant benefit to the patient.

Submitted by Chris Cosgrove, Orthopedic Surgery PGY-2

Faculty Reviewed by : Lukas Zebala, MD, Assistant Professor, Orthopaedic Surgery

Everyday EBM Editor Maia Dorsett (@maiadorsett)

References:

1. Venkatesan, M., Fong, A., & Sell, P. J. (2012). CT scanning reduces the risk of missing a fracture of the thoracolumbar spine. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume, 94(8), 1097-1100.

2. Sixta, S., Moore, F. O., Ditillo, M. F., Fox, A. D., Garcia, A. J., Holena, D., ... & Cotton, B. (2012). Screening for thoracolumbar spinal injuries in blunt trauma: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 73(5), S326-S332.

3. Karul, M., Bannas, P., Schoennagel, B. P., Hoffmann, A., Wedegaertner, U., Adam, G., & Yamamura, J. (2013). Fractures of the thoracic spine in patients with minor trauma: Comparison of diagnostic accuracy and dose of biplane radiography and MDCT. European journal of radiology, 82(8), 1273-1277.

4. Homnick, A., Lavery, R., Nicastro, O., Livingston, D. H., & Hauser, C. J. (2007). Isolated thoracolumbar transverse process fractures: call physical therapy, not spine. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 63(6), 1292-1295.

5. Bradley, L et al. Isolated transverse process fractures: spine service management not needed. J Trauma 2008 Oct; 65(4):832-6.